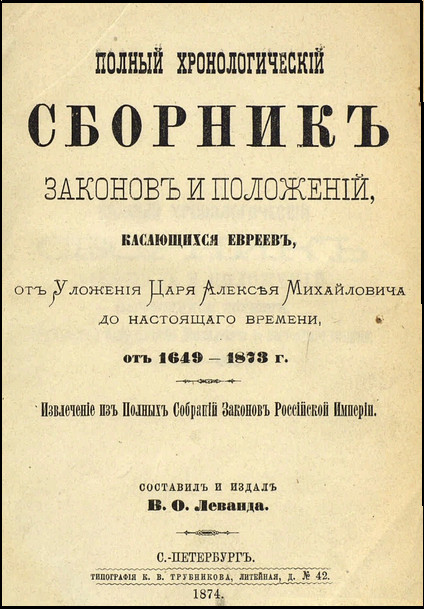

Russian Laws and Establishment of the Pale: Excerpts from the "Levanda Index"

V.O. Levanda, The complete chronological collection of laws and legal positions concerning the Jews: from the Legal Code of Czar Alexsei Mikailovich to the present time, 1649-1873, St. Petersburg, 1874.

Introduction

While Jews are known to have resided in Russia since the middle ages and suffered various attacks and abuses, records show that they had been subjected to discriminatory laws by the t'sars since at least the 17th century. A number of royal decrees from this period intended to expel the Jews westward to the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. In the late 18th century when Catherine II conspired with Austria and Prussia to carve up (partition) the Commonwealth, large numbers of Jews were suddenly living within the Russian state (1772). Expulsion of this size population would have been unthinkable. Moreover, Catherine II was an Enlightenment thinker who did not quite share the anti-Semitism of her predecessors. She ensured freedom of religion, and actually invited various foreigners (among them Jews) into Russia to colonize Novorossiya, the recently conquered Black Sea region (1769). Nevertheless, by 1790 pressures from Russia's merchant class compelled her to limit the rights of Russia's Jews in a determined fashion and she restricted them to reside and trade where they had done so before the partition, but included the Black Sea region in the decree. This ruled out the Russian interior, and expressly excluded them from Smolensk and Moscow. What began in 1791 as a way to control the Jews economically became the basis for a continuing body of legislation to regulate a specific geographic area for Jewish life known as the (Черта постоянной еврейской оседлости) Cherta postoyannoy yevreyskoy osedlosti, or Pale of Permanent Jewish Settlement. Over the course of the 19th century these laws were intended to stifle Jewish enrichment by limiting their ability to compete in the marketplace, protect the peasantry from presumed exploitation and generally disempower the Jewish masses. These regulations were some of the most obvious factors in the Jews' burgeoning impoverishment.

In 1874 a compendium of laws dedicated to recording Jewish regulatory statutes was published by V.O. Levanda, himself a lawyer and Jewish. Levanda had been encouraged to publish the catalog by Baron Horace Guenzburg. He gathered specific texts from other codes of law that pertained expressly to Jewish subjects and compiled them into his catalog. As the title suggests the laws are arranged chronologically, following the succession of the t'sars, with each page headed by the name of the current reigning Emperor. It is worth noting that Horace Guenzburg's father, Joseph Yosel Guenzburg, is in fact credited with winning the right of permanent legal settlement outside the Pale in 1865 by Jews of qualifying status.

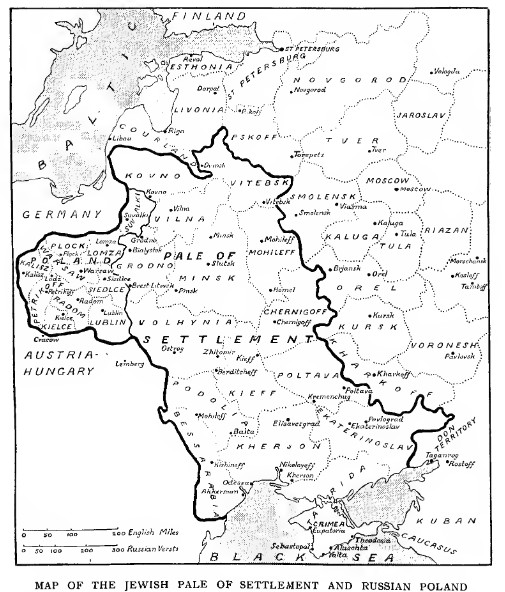

By following the laws in Levanda's collection we can trace the changing boundaries of Jewish residence: first by expulsion from the western edge of the Empire and then by successive changes after the 1772 partition. These laws of the 19th century follow a pattern of increasing frequency, detailed language and discriminatory intensity. Codification of Jewish rights or the lack thereof increased dramatically over the reign of Nicolas I (1825-1855). The opening of the Russian interior to Jewish residence took place during the reign of Alexander II as mentioned above, but with excessive stipulations and numerous challenges for revocation. Discriminatory laws reached their peak at late century during the reign of Alexander III in the aftermath of the assassination of his father, Alexander II. This unfortunate event precipitated the so called May laws of 1882. In The Legal Sufferings of the Jews in Russia, published by Lucian Wolf in 1912, we find a detailed account of all the damning restrictions put forth to further wear down the Jewish population starting with the May laws. The appendix of the book enumerates those restrictions beginning in 1882 through to 1903. In the frontispeice is the map at left, the most commonly seen rendition of the Pale. In fact it is a combination of "Russian Poland" and the Pale. Russian Poland, or Congress Poland and the Pale had similar laws limiting Jew's rights but these statutes were written for each region separately and Jews were not permitted to transit between the two areas until the second half of the 19th century. The "Pale" grew gradually, up until 1818 with the addition of the Bessarabian oblast (region), then receded in 1825 and again in 1887. While Wolf gives us perhaps the final legal picture of the Jews in the Pale, he also reports on Jews who were priviledged to live outside its boundary. They were at constant risk of deportation back inside its limit, due in large part to the May laws.

In this section of the website, we offer texts of laws which trace the development of the Pale, following various expulsions and restrictions of Jewish residential and occupational rights. In some cases maps are linked to the regulations charting these rules. Expulsion, often forgotten in popular memory as a form of violence against the Jews, is chronicled in these pages from the 17th century through the 19th. Several expulsion decrees, applied within the Pale itself, led to extreme hardship for tens of thousands of families and no doubt, loss of life. An additional source of translations of these laws and decrees, with excellent historical notes, can be found here, Our translations have been configured to appear like the original Levanda texts using similar fonts and typeface. This work has been generously funded by the Memorial Foundation for Jewish Culture in New York City.